An energy-intensive sector

The mining industry is responsible for a significant energy consumption and is an important source of greenhouse gas emissions. This sector currently accounts for roughly 1.7% of the global energy consumption, which is likely to increase up to 8% by 2060 [1].

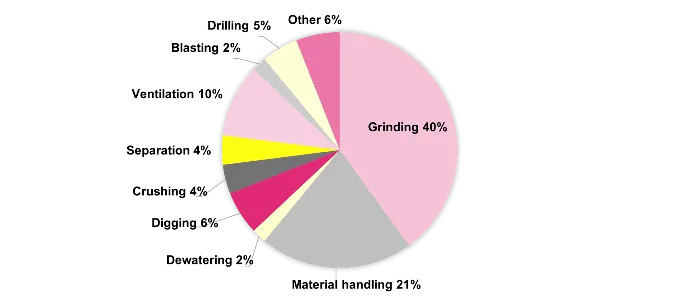

A breakdown of the energy consumption in the USA, shows that grinding and crushing accounts approximately for 50% of the total, followed by material handling; see Figure 1.

The Discrete Element Method (DEM), originally developed by Cundall and Strack [3] for rock mechanics and geotechnical applications, has been extensively used to simulate mining and mineral processes. Applications include bulk material handling, screening separation, crushing and equipment wear.

In this article, three main applications are addressed: earth movement, equipment wear, and particle screening.

Figure 1: breakdown of the energy consumption for the mining sector in the USA. [2]

Earth movement - the dragline excavator

One of the largest earth-moving equipment existing is the dragline excavator, which is commonly used in surface mining and construction operations. It features a large bucket suspended from a long, truss-like boom, controlled through two main cables: the hoist rope and the drag rope.

During a typical excavation cycle, the hoist rope lowers the bucket onto the material. The drag rope then pulls the bucket along the ground to collect the material. Once filled, the bucket is lifted using the hoist rope, moved horizontally to the dumping location, and emptied by releasing the drag rope, which tilts the bucket and discharges its contents.

The DEM simulation in the left video shows the dragline bucket of a Liebherr HS8100.2 crawler crane excavating gravel. The bucket and lifting beam are modeled as 6-degrees-of-freedom (6-dof) geometries, while the chains and ropes are modeled as bonded spherical particles. The motion of the assembly is controlled by translating the attachments to the hoist rope (top) and to the drag rope (right). The thinner rope connecting the drag rope with the top of the bucket can slide on the pulley and therefore control the tilting of the bucket.

Video 1: DEM simulation of a dragline excavator. CAD geometry of the bucket from “1/14 scale dragline bucket for liebherr hs 855 or 8100” by raoul00123 on cults3d.com - Licensed under CC BY.

Equipment wear

Mechanical wear is ubiquitous in mining and drastically affects the equipment's service life and maintenance routine. Two pieces of equipment that are particularly affected by wear are the transfer chute and the ball mill.

Transfer chutes are used in belt conveying systems to accelerate bulk material or direct material flow from one conveyor to another. Proper chute design is essential to ensure efficient material transfer, minimizing spillage, blockage, and wear on both the chute and conveyor belt.

The DEM simulation in the right video shows a bulk material flowing from a top conveyor to a bottom one (magenta) through a transfer chute. The wear has been represented by using the Finnie model and by following an unresolved approach (i.e., the mesh is not deformed). As can be seen, two parts in the transfer chute are particularly subjected to wear, namely the hood and the spoon. The hood is an upper, curved deflector that catches material from an upper conveyor and redirects it downwards, while the spoon is a lower, curved receiving chute that gently guides the material from the hood and deposits it centrally and smoothly onto the lower conveyor belt.

Video 2: The DEM simulation, performed with Aspherix®, shows a bulk material flowing from a top conveyor belt to a bottom one (magenta) through a transfer chute.

Video 3: The DEM simulation, performed with Aspherix®, shows a of a ball mill's section where a mix of steel balls (grey spherical particles) and rocks (brown non-spherical particles) is processed.

A ball mill is a device used to grind and blend materials (e.g., ores) by means of steel or ceramic balls. The inner surface of the tumbler is sensitive to wear and therefore covered with an abrasion-resistant material (liner).

The DEM simulation in the left video shows the section of a ball mill where a mix of steel balls (grey spherical particles) and rocks (brown non-spherical particles) is processed. The wear has been represented by using the Finnie model and by following a resolved approach (i.e., the mesh is deformed as the simulation proceeds). Since the wear alters the liner's geometry, and therefore the grinding efficiency of the device, it is necessary to properly resolve the mesh deformation over time.

Since wear can arise from multiple mechanisms - including erosion, abrasion, and impact deformation - accurately modelling wear remains challenging. The upcoming Aspherix® 7.0 release, scheduled for later this year, will introduce a new wear model combining different source mechanisms for more accurate predictions.

Particle screening

Vibratory screeners are industrial machines used to sort a bulk material based on the particle size. Systems used in mining operations are capable of screening thousands of tons of material per hour. These machines typically comprise several decks of screens with different hole sizes and having a vibratory motion.

The DEM simulation in the right video shows a simplified screener sorting convex, stone-shaped particles. The material is fed in from the top right onto a slanted, oscillating grate. Smaller particles fall through and exit left via a conveyor, while larger ones are carried along the grate and exit right.

Conclusions

DEM plays an important role in the modelling of mining applications and Aspherix® offers a competitive feature-set to enhance that, namely:

1. Shape: supporting different particles sizes (sphere, superquadric, convex, etc.)

2. Wear: State-of-the-art modelling of equipment wear

3. Mesh: Complex geometry motion (6dof, mesh motion, etc.)

4. Run-time: computationally-efficient and both CPU- and GPU-enabled

Do you want to know more? Request a free trial or contact us directly!

1. Aramendia, Emmanuel, et al. "Global energy consumption of the mineral mining industry: Exploring the historical perspective and future pathways to 2060." Global Environmental Change 83 (2023): 102745.

2. U.S. DOE. (2007). Mining industry energy bandwidth study. Washington, United States: U.S. Department of Energy.

3. Cundall, P. A., and O. D. L. Strack. "Discussion: A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies." Géotechnique 30.3 (1980): 331-336.